HSE Researchers Discover Simple and Reliable Way to Understand How People Perceive Taste

A team of scientists from the HSE Centre for Cognition & Decision Making has studied how food flavours affect brain activity, facial muscles, and emotions. Using near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), they demonstrated that pleasant food activates brain areas associated with positive emotions, while neutral food stimulates regions linked to negative emotions and avoidance. This approach offers a simpler way to predict the market success of products and study eating disorders. The study was published in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

How do we perceive taste? Why do some foods bring pleasure, while others evoke indifference or even aversion? Science has established that this is related to the activation of specific brain regions that process our perception of taste and emotions. For instance, sweet flavours can stimulate areas associated with pleasure, while bitter flavours activate regions responsible for alertness and defence against potential danger.

To investigate these processes, scientists traditionally use complex and expensive methods. Functional MRI (fMRI) is considered the most effective, as it allows researchers to ‘look inside’ the brain and observe which parts are activated by different tastes. However, such technologies require strict conditions: participants must remain motionless, which can interfere with the perception of food.

Researchers at HSE University successfully demonstrated how fNIRS can be used to study taste perception. This method is cheaper, easier to use, and allows participants to remain in a natural position, such as sitting at a table. However, fNIRS has rarely been applied to taste research, and its capabilities remain underexplored.

During the experiment, the scientists not only tested how effectively fNIRS captures brain responses to taste but also analysed how this activity is connected to other physiological processes. The researchers measured heart rate, skin response (electrodermal activity), and recorded facial muscle movements to obtain a comprehensive picture of how we react to the taste of food.

‘We tested the response to two types of food in 36 volunteers: pleasant (fruit puree) and neutral (vegetable puree). The choice of puree was deliberate: the soft texture helped avoid data distortion that could have arisen from chewing. As expected, the vegetable puree did not evoke excitement, but it would be incorrect to call it unpleasant food. If we rank all food, it falls into either pleasant or neutral categories. Truly “unpleasant” food, in essence, does not exist,’ explained Julia Eremenko, Research Fellow at the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience and one of the study’s authors.

Using a special fNIRS setup, the researchers targeted the insular cortex, a brain region deep within the temporal lobe responsible for taste perception. While fMRI is typically required to study this area, the modified fNIRS method enabled brain activity to be analysed with simpler equipment.

The researchers achieved significant progress in studying how the brain responds to food. One of the key accomplishments was the use of a specialised setup for near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which allowed them to focus on the insular cortex. This brain region, located deep within the temporal lobe, is responsible for taste perception. Typically, studying this area requires magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but the modified fNIRS method enabled brain activity analysis using less complex equipment.

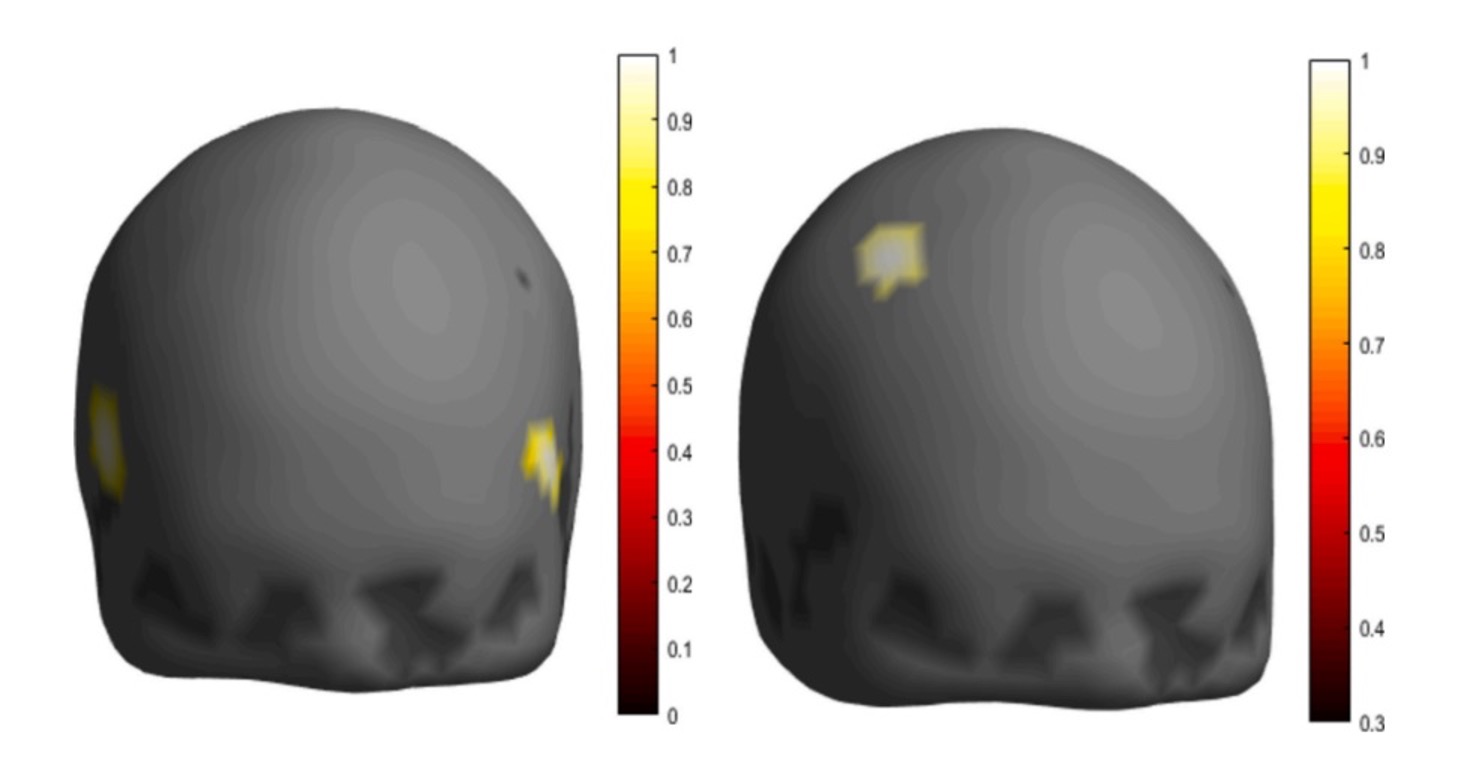

The results showed that pleasant food activated the insular cortex in the left hemisphere of the brain, which is associated with positive emotions and feelings of pleasure. Neutral flavours, on the other hand, activated the right precentral gyrus. This phenomenon is explained by interhemispheric asymmetry—a characteristic of brain function where each hemisphere processes different types of stimuli. The left hemisphere predominantly responds to positive emotions, while the right is associated with processing negative stimuli and avoidance reactions. Thus, the vegetable puree elicited unpleasant emotions in participants.

The researchers also recorded how food perception was reflected in the participants' facial expressions. Pleasant food activated the zygomaticus major muscle, responsible for smiling. In contrast, neutral food caused activation of the corrugator muscle, which furrows the brow before swallowing.

These physiological reactions are so reliable that they can be used to objectively assess taste preferences. Unlike verbal feedback, which can be subjective or insincere, facial reactions provide an honest indication of whether someone enjoys the food. Moreover, the method is simple and efficient: testing just 40–50 people is sufficient to draw conclusions. Such data can be valuable for food companies looking to improve their products.

‘We are actively studying how neurophysiological stimuli influence food perception. For instance, at our institute, we have developed a food delivery system integrated with neurophysiological equipment. This system is synchronised with experimental designs, allowing us to analyse the impact of packaging or price on taste perception. Additionally, my colleagues and I run a Rutube channel on neuromarketing where we share insights on how brain science can be used to effectively promote products and services, as well as to gain a deeper understanding of consumer motives and behaviour,’ explained Julia Eremenko.

The research was conducted as part of the strategic project 'Human Brain Resilience: Neurocognitive Technologies for Adaptation, Learning, Development and Rehabilitation in a Changing Environment' (‘Priority 2030’).

Julia Eremenko

See also:

Mortgage and Demography: HSE Scientists Reveal How Mortgage Debt Shapes Family Priorities

Having a mortgage increases the likelihood that a Russian family will plan to have a child within the next three years by 39 percentage points. This is the conclusion of a study by Prof. Elena Vakulenko and doctoral student Rufina Evgrafova from the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences. The authors emphasise that this effect is most pronounced among women, people under 36, and those without children. The study findings have been published in Voprosy Ekonomiki.

Scientists Discover How Correlated Disorder Boosts Superconductivity

Superconductivity is a unique state of matter in which electric current flows without any energy loss. In materials with defects, it typically emerges at very low temperatures and develops in several stages. An international team of scientists, including physicists from HSE MIEM, has demonstrated that when defects within a material are arranged in a specific pattern rather than randomly, superconductivity can occur at a higher temperature and extend throughout the entire material. This discovery could help develop superconductors that operate without the need for extreme cooling. The study has been published in Physical Review B.

Scientists Develop New Method to Detect Motor Disorders Using 3D Objects

Researchers at HSE University have developed a new methodological approach to studying motor planning and execution. By using 3D-printed objects and an infrared tracking system, they demonstrated that the brain initiates the planning process even before movement begins. This approach may eventually aid in the assessment and treatment of patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s. The paper has been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Civic Identity Helps Russians Maintain Mental Health During Sanctions

Researchers at HSE University have found that identifying with one’s country can support psychological coping during difficult times, particularly when individuals reframe the situation or draw on spiritual and cultural values. Reframing in particular can help alleviate symptoms of depression. The study has been published in Journal of Community Psychology.

Scientists Clarify How the Brain Memorises and Recalls Information

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has demonstrated for the first time that the anterior and posterior portions of the human hippocampus have distinct roles in associative memory. Using stereo-EEG recordings, the researchers found that the rostral (anterior) portion of the human hippocampus is activated during encoding and object recognition, while the caudal (posterior) portion is involved in associative recall, restoring connections between the object and its context. These findings contribute to our understanding of the structure of human memory and may inform clinical practice. A paper with the study findings has been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Researchers Examine Student Care Culture in Small Russian Universities

Researchers from the HSE Institute of Education conducted a sociological study at four small, non-selective universities and revealed, based on 135 interviews, the dual nature of student care at such institutions: a combination of genuine support with continuous supervision, reminiscent of parental care. This study offers the first in-depth look at how formal and informal student care practices are intertwined in the post-Soviet educational context. The study has been published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education.

AI Can Predict Student Academic Performance Based on Social Media Subscriptions

A team of Russian researchers, including scientists from HSE University, used AI to analyse 4,500 students’ subscriptions to VK social media communities. The study found that algorithms can accurately identify both high-performing students and those struggling with their studies. The paper has been published in IEEE Access.

HSE Scientists: Social Cues in News Interfaces Build Online Trust

Researchers from the HSE Laboratory for Cognitive Psychology of Digital Interface Users have discovered how social cues in the design of news websites—such as reader comments, the number of reposts, or the author’s name—can help build user trust. An experiment with 137 volunteers showed that such interface elements make a website appear more trustworthy and persuasive to users, with the strongest cue being links to the media’s social networks. The study's findings have been published in Human-Computer Interaction.

Immune System Error: How Antibodies in Multiple Sclerosis Mistake Their Targets

Researchers at HSE University and the Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IBCh RAS) have studied how the immune system functions in multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease in which the body's own antibodies attack its nerve fibres. By comparing blood samples from MS patients and healthy individuals, scientists have discovered that the immune system in MS patients can mistake viral proteins for those of nerve cells. Several key proteins have also been identified that could serve as new biomarkers for the disease and aid in its diagnosis. The study has been published in Frontiers in Immunology. The research was conducted with support from the Russian Science Foundation.

Scientists Develop Effective Microlasers as Small as a Speck of Dust

Researchers at HSE University–St Petersburg have discovered a way to create effective microlasers with diameters as small as 5 to 8 micrometres. They operate at room temperature, require no cooling, and can be integrated into microchips. The scientists relied on the whispering gallery effect to trap light and used buffer layers to reduce energy leakage and stress. This approach holds promise for integrating lasers into microchips, sensors, and quantum technologies. The study has been published in Technical Physics Letters.